This is a new blog that we have started for families who are in need of help.

This blog has been started by two wonderful volunteers, Stephanie and Jessica and we are so happy to have their help.

To read the stories about people in need please go to this link.http://familyaidprogram.blogspot.com/

If you are able to help any of these people, even a little , it will mean a great deal to them.

Thanks.

A Look At the Overlooked

Hi all. It’s Ronnie. I have wanted to write to you all week, but I have been overwhelmed with a kind of work that couldn’t wait. It’s been really hard to set aside time when the truth is that I can always be doing more here to help.

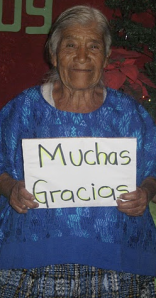

Our first working day with Mayan Families, I was asked if I could go on a lunch run for the new Elderly Feeding Program. They wanted me to help check up on all the participants, see how they were doing health-wise and if they needed any special attention. I had never worked with elderly persons or in any sort of health service, and to be honest I had never really taken much interest in that sort of thing—but there didn’t seem to be anyone else available, so I of course said yes. So I hopped into the tuk tuk [a three-wheel rickshaw used as a taxi] with Seño Estela, the cook, and our driver Oscar, and off we went (each under piles of food).

After a short ride, we jumped out of the tuk tuk and weaved through narrow pedestrian streets and alleyways. Surrounded by windowless, tin-roofed, cinderblock and wood shanties, everything looked the same to me. But Seño Estela and Oscar reached the first stop without hesitation. We yelled Buenas tardes (Good afternoon) as we passed the fence and walked through the doorless entrance. It was damp, dim, and cramped, and the dirt floor was speckled with empty buckets and containers. Apparently this room was the kitchen, but that fact wasn’t indicated by the presence of any food. We were welcomed with the tired smile of a middle-aged woman wearing traje and a dirty apron. She called us into the adjacent bedroom, where a very pale, old woman lay in bed, seemingly dazed, under a dirty blanket. The walls were covered in tarp in a weak attempt to keep out the draft that crept through the gaps in the wooden plank walls. 83-year-old Josefa Quechi stirred and (although I explained it wasn’t necessary) with slow and painful intention rotated to face us. The notebook I had with me read: “No puede caminar porque sus piernas le duelen . . . Por el momento se encuentra tomando medicamentos” (“Unable to walk because her feet hurt . . . Currently taking medication.”) But in a short conversation with Josefa’s daughter, I learned that Josefa had actually dislocated her hip ten months ago.

-Tomaba medicina, pero ya terminó. (She took medicine, but it has run out.)

-Hace cuanto tiempo que ella no tiene medicina para dolor? (For how long hasn’t she had pain medicine?)

-Hace algunas semanas—es que no tengo dinero para comprarla. (Weeks—It’s that I don’t have money to buy it.)

Made nervous by the fact that the binder was outdated, I made a note to be very thorough in my questioning with everyone we were going to visit. I asked for Josefa’s history and if anything else ailed her. After that I wrote down the medicines and help that Josefa needed. We left lunch on the table and said Hasta mañana (See you tomorrow), squinting as the sun hit our eyes upon exiting the dark space. Visiting Josefa was not nearly the most shocking thing I experienced that day. There was disease and visible hunger and profound loneliness. There was a family of 8, including 2 severely disabled persons, sharing a cramped and windowless room. There was an old man living in what was essentially a closet. Almost without exception, every person that we visited had pain—in some cases debilitating—and no pain medicine. I collected unfilled prescriptions (the public health clinic here offers free checkups, but hardly has any medicines to hand out) and made a note of who needed urgent medical care. There were untreated infections, unchecked chest pains, and terrible stomach aches. I quickly stopped expecting any form of dental or general bodily hygiene. I also learned that this lunch that we were bringing was in many cases the only thing that some of these people ate all day. They would try to make Friday’s lunch last the weekend.

The next day we did the same run, but this time I delivered filled prescriptions and told a number of the ancianos (elderly persons) that we could go to the doctor (or, in the case of the bedridden, bring the doctor or nurse to them). That afternoon we took a nurse to the ancianos who were in the worst condition. On Wednesday after the lunch and medicines delivery run, I picked up several ancianos to take them to the health clinic. Mayan Families has a very tight budget, and so our first stop is almost always the public health clinic. Through its Elderly Care Program, Mayan Families does all it can, but we have so little funding that I walk blocks and blocks to different pharmacies in order to save (the equivalent of) 30 cents on drugs. It is a constant struggle, and a terrible thing to have to decide who will receive our help and who will not.

I’m going to be especially candid in this post. As I mentioned before, I’m an economics major and statistics minor, and I think mathematically. I always consider return on investment, and with almost everything I do, I choose the path of highest return. If you had asked me a few months ago whether I would be interested in dedicating some of my resources to elderly care, I would have said yes, perhaps, but I admit that in the back of my mind I would have been thinking that it would make more sense to focus efforts on children, who can grow up to build a better standard of living. In the past few weeks I have realized that some things are much more simple. The right of every person to a dignified existence, and our obligation to do our best to reduce the suffering of others, regardless of the demographic—those have become absolutely simple concepts to me ever since I came face to face with raw suffering.

I have updated the blog for Mayan Families’ Elderly Care Program, where you can read about some of the elders in our program, and, most importantly, where you can elect to sponsor an individual or make a one-time donation (please enter “Elderly Care” into the other section). General donations would go to ensuring that we always have a supply of food, medicine, adult diapers, blankets, and funds for transportation and medical services. You can ask for your one-time donation to go to our Elderly Care Shelter Fund, which will help us to secure homes for the homeless and better homes for people like Pedro. You can also ask for your one-time donation to go to our Elderly Care Medical Fund, which will help us to ensure that everyone gets the medical treatment that they need. This program has very little overhead, and 100% of the donation that you make will end up with our elderly members. I’ll be talking more about this program and its members later, but we could really use your help now. You can truly make an immediate, dramatic impact on someone’s life.

Our first working day with Mayan Families, I was asked if I could go on a lunch run for the new Elderly Feeding Program. They wanted me to help check up on all the participants, see how they were doing health-wise and if they needed any special attention. I had never worked with elderly persons or in any sort of health service, and to be honest I had never really taken much interest in that sort of thing—but there didn’t seem to be anyone else available, so I of course said yes. So I hopped into the tuk tuk [a three-wheel rickshaw used as a taxi] with Seño Estela, the cook, and our driver Oscar, and off we went (each under piles of food).

After a short ride, we jumped out of the tuk tuk and weaved through narrow pedestrian streets and alleyways. Surrounded by windowless, tin-roofed, cinderblock and wood shanties, everything looked the same to me. But Seño Estela and Oscar reached the first stop without hesitation. We yelled Buenas tardes (Good afternoon) as we passed the fence and walked through the doorless entrance. It was damp, dim, and cramped, and the dirt floor was speckled with empty buckets and containers. Apparently this room was the kitchen, but that fact wasn’t indicated by the presence of any food. We were welcomed with the tired smile of a middle-aged woman wearing traje and a dirty apron. She called us into the adjacent bedroom, where a very pale, old woman lay in bed, seemingly dazed, under a dirty blanket. The walls were covered in tarp in a weak attempt to keep out the draft that crept through the gaps in the wooden plank walls. 83-year-old Josefa Quechi stirred and (although I explained it wasn’t necessary) with slow and painful intention rotated to face us. The notebook I had with me read: “No puede caminar porque sus piernas le duelen . . . Por el momento se encuentra tomando medicamentos” (“Unable to walk because her feet hurt . . . Currently taking medication.”) But in a short conversation with Josefa’s daughter, I learned that Josefa had actually dislocated her hip ten months ago.

-Tomaba medicina, pero ya terminó. (She took medicine, but it has run out.)

-Hace cuanto tiempo que ella no tiene medicina para dolor? (For how long hasn’t she had pain medicine?)

-Hace algunas semanas—es que no tengo dinero para comprarla. (Weeks—It’s that I don’t have money to buy it.)

Made nervous by the fact that the binder was outdated, I made a note to be very thorough in my questioning with everyone we were going to visit. I asked for Josefa’s history and if anything else ailed her. After that I wrote down the medicines and help that Josefa needed. We left lunch on the table and said Hasta mañana (See you tomorrow), squinting as the sun hit our eyes upon exiting the dark space. Visiting Josefa was not nearly the most shocking thing I experienced that day. There was disease and visible hunger and profound loneliness. There was a family of 8, including 2 severely disabled persons, sharing a cramped and windowless room. There was an old man living in what was essentially a closet. Almost without exception, every person that we visited had pain—in some cases debilitating—and no pain medicine. I collected unfilled prescriptions (the public health clinic here offers free checkups, but hardly has any medicines to hand out) and made a note of who needed urgent medical care. There were untreated infections, unchecked chest pains, and terrible stomach aches. I quickly stopped expecting any form of dental or general bodily hygiene. I also learned that this lunch that we were bringing was in many cases the only thing that some of these people ate all day. They would try to make Friday’s lunch last the weekend.

The next day we did the same run, but this time I delivered filled prescriptions and told a number of the ancianos (elderly persons) that we could go to the doctor (or, in the case of the bedridden, bring the doctor or nurse to them). That afternoon we took a nurse to the ancianos who were in the worst condition. On Wednesday after the lunch and medicines delivery run, I picked up several ancianos to take them to the health clinic. Mayan Families has a very tight budget, and so our first stop is almost always the public health clinic. Through its Elderly Care Program, Mayan Families does all it can, but we have so little funding that I walk blocks and blocks to different pharmacies in order to save (the equivalent of) 30 cents on drugs. It is a constant struggle, and a terrible thing to have to decide who will receive our help and who will not.

I’m going to be especially candid in this post. As I mentioned before, I’m an economics major and statistics minor, and I think mathematically. I always consider return on investment, and with almost everything I do, I choose the path of highest return. If you had asked me a few months ago whether I would be interested in dedicating some of my resources to elderly care, I would have said yes, perhaps, but I admit that in the back of my mind I would have been thinking that it would make more sense to focus efforts on children, who can grow up to build a better standard of living. In the past few weeks I have realized that some things are much more simple. The right of every person to a dignified existence, and our obligation to do our best to reduce the suffering of others, regardless of the demographic—those have become absolutely simple concepts to me ever since I came face to face with raw suffering.

I have updated the blog for Mayan Families’ Elderly Care Program, where you can read about some of the elders in our program, and, most importantly, where you can elect to sponsor an individual or make a one-time donation (please enter “Elderly Care” into the other section). General donations would go to ensuring that we always have a supply of food, medicine, adult diapers, blankets, and funds for transportation and medical services. You can ask for your one-time donation to go to our Elderly Care Shelter Fund, which will help us to secure homes for the homeless and better homes for people like Pedro. You can also ask for your one-time donation to go to our Elderly Care Medical Fund, which will help us to ensure that everyone gets the medical treatment that they need. This program has very little overhead, and 100% of the donation that you make will end up with our elderly members. I’ll be talking more about this program and its members later, but we could really use your help now. You can truly make an immediate, dramatic impact on someone’s life.